When the Discayas told the Senate Blue Ribbon Committee, “We’ve been in business for 23 years, so of course we’ve earned,” critics quickly pounced, dismissing it as an exaggeration or worse, a fabrication. But that soundbite, stripped of context, deserves a closer, fairer look.

The Spirit of “23 Years”

Fact-checkers have pointed out that the Discaya corporations on paper were incorporated only in the last 10–11 years. True. But critics miss the bigger point: business experience doesn’t begin on the day SEC papers are filed.

The Discayas’ family has been in contracting, trading, and small-scale construction for decades—long before Alpha & Omega or St. Timothy were incorporated. Formal registration may have come in 2014, but the enterprise spirit traces back much earlier. In Philippine business culture, “23 years in the industry” often refers not just to corporate filings but to the cumulative years of active business engagement.

To reduce the claim to mere dates on paper is to ignore lived experience.

⸻

Contracts Are Opportunities, Not Crimes

Critics highlight the billions in flood-control projects awarded to Discaya companies as if these were automatic proof of wrongdoing. But isn’t that the point of government procurement? To open opportunities for qualified contractors, big or small?

Yes, the Discayas have secured ₱31–32 billion in projects from 2022 to 2025. That is not evidence of “impossible profit.” That is evidence of trust from government agencies that followed bidding procedures. To argue that contracts are equivalent to corruption is to undermine the very framework of public bidding itself.

⸻

Profitability in Context

Skeptics compare the Discayas to giants like Megawide or EEI and say, “If even they struggle, how could smaller firms earn billions?” The answer: overhead.

Publicly listed conglomerates carry massive capital, debt, and diversified operations. Their margins are thin because they manage airports, railways, or international projects. A leaner contractor, focused on specific DPWH contracts, can, in fact, yield better margins precisely because it isn’t burdened by corporate sprawl.

Critics apply the wrong benchmark. It’s like comparing a sari-sari store with SM Supermalls: different structures, different cost bases, different dynamics.

⸻

On Blacklists and Scrutiny

Yes, some Discaya firms have faced blacklisting or investigation. But blacklisting in the DPWH context is often provisional, administrative, and reversible—not a final judgment of corruption. Many established contractors have been flagged and later cleared. To single out the Discayas without context is selective judgment.

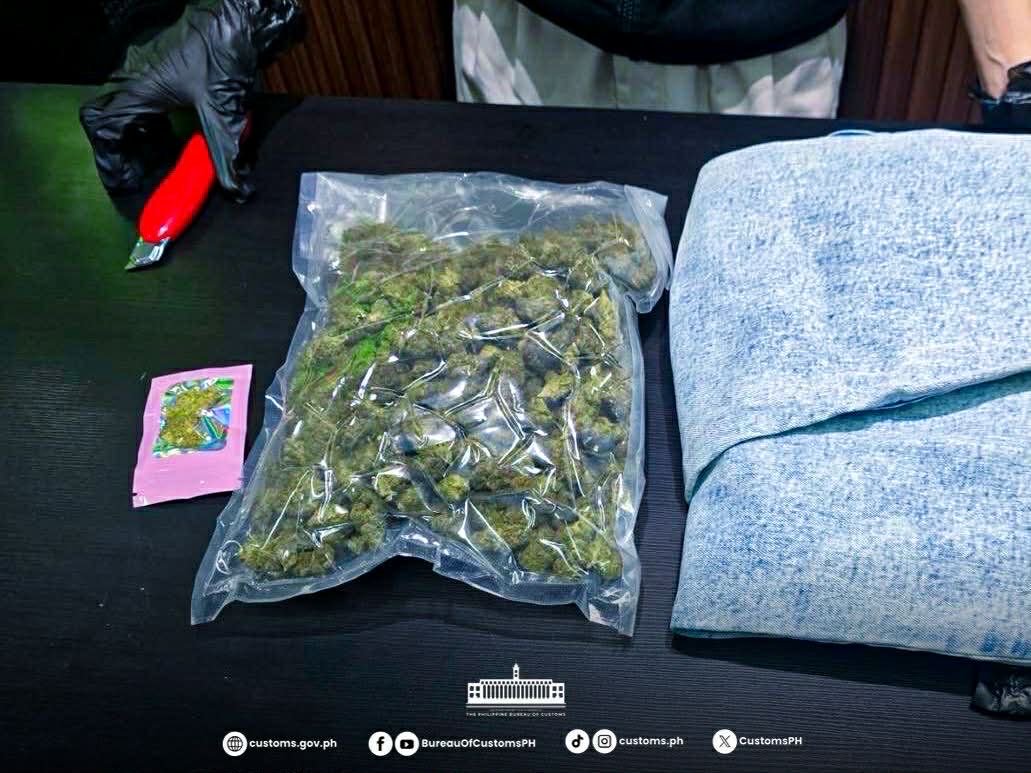

As for the BIR and Customs inquiries, these are standard procedures for any high-profile contractors whose lifestyles draw public attention. Investigations are not convictions. The presumption of innocence must hold until due process is complete.

⸻

The Bigger Picture

At its heart, the debate is about perception versus reality:

•Were the Discayas exaggerating with “23 years”? Maybe. But they were pointing to a long entrepreneurial journey, not just SEC paperwork.

•Do contracts equal guaranteed profit? No, but they do show competitiveness and capability.

•Do blacklists and probes equal guilt? No, they are part of the checks and balances every contractor faces.

The Discayas may not be perfect. But dismissing them outright as frauds because their success seems “too big, too fast” is unfair. In fact, their story reflects the aspirations of many Filipino entrepreneurs who, after years of hustling in small businesses, finally break through to the big leagues.

The Fair Truth

Strip away the noise, and here’s what remains:

•The Discayas’ claim of “23 years” is a shorthand for family business experience, not just SEC records.

•Billions in contracts are not proof of theft but of opportunity granted by due process.

•Lean contractors can, in fact, earn more relative to size than sprawling conglomerates.

•Scrutiny is normal—but guilt must be proven, not presumed.

The Senate soundbite may have sounded boastful, but behind it is a narrative of persistence, growth, and ambition. Instead of rushing to condemn, perhaps we should ask: are we uncomfortable with the Discayas’ success because of what they did, or simply because of how fast they rose?

Sometimes, envy—not evidence—drives the harshest criticism.

Spread the news